House Research

The Street

The setting for our Site Specific performance is a house on West Parade, Lincoln, to the west of the city centre. It was built in 1932, the date proudly displayed on the house itself, but beyond that the history of the house is a mystery.

A trip to the Lincolnshire Archives reveals that as far back as 1842 West Parade was actually called Clay Lane, after the clay pits which were used during that era. Though the house does not lie on top of any of these pits, it may be worth experimenting with clay as part of the performance process as it relates to the street and the pits played an important part in the building boom of the 1870s and 1880s producing bricks and tiles which were used all over the country.

It transpires that the current job centre on the corner of West Parade and Orchard Street used to be the site of St Martin’s Church, which was built in c.1873. The vicars of the church lived in the vicarage which is still situated near to the house we are using, so a religious theme could be a performance route.

Above: St Martin’s Church ((Parkinson, Wendy (unknown) Lincoln St Martin New (original: Lincolnshire Echo) [Online] Available at: http://www.wparkinson.com/Churches/City%20photos/Lincoln%20St%20Martin%20new.jpg (Accessed: 25th February 2013). ))

Another near neighbour, around the time our house was built, was the Oxford House Private School, Preparatory for Girls and Boys and run by Principal Miss Brunner. It may be worth researching the school as it was open from at least 1932-46. The idea of a private school within a house could be an interesting concept to explore.

In the 1946 Lincoln Directories there is finally a reference to our house. In the house next door there is a James Alfred Wright and in our house there is an Alfred Ernest Revill aged 66.

Alfred Ernest Revill

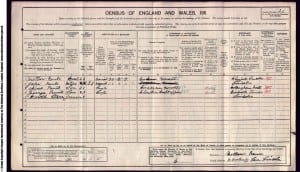

Above: 1911 Census record for Alfred Revill ((‘Alfred Revill’ (1911) Census return for Motherby Lane, Lincoln, Lincolnshire. Public Record Office: PRO RG14/19744, folio 51, p.3. Find My Past (2013) Available at: http://www.findmypast.co.uk (Accessed: 21st February 2013). ))

Looking at the censuses I managed to discover some information on Alfred Revill. He was born in 1880 in South Collingham, Nottinghamshire. His parents were Matthew (age 35), a Groom, and Julia (age 25) and he was the second child of the six they had. Surprisingly, all his siblings lived into adulthood.

Alfred’s parents were born in Lincoln, although in the 1881 Census, they were living in Binbrook, Louth. ((‘Alfred Revill’ (1881) Census return for Binbrook, Louth, Lincolnshire. Public Record Office: PRO RG11/3264, folio 35, p.16. Find My Past (2013) Available at: http://www.findmypast.co.uk (Accessed: 21st February 2013). )) By 1891 they had moved back to Lincoln and were registered at 8 Winnowsty Buildings, Winnowsty Lane. By this time (when Alfred was 11) all of his brothers and sisters had been born:

- John J. Revill, born 1878

- Alfred E. Revill, born 1880

- Blanche M. Revill, born 1881

- Elizabeth A. Revill, born 1883

- Walter N. Revill, born 1886

- George H. Revill, born 1888

The eldest son John, aged 13, was working as an Errand Boy while Alfred and the rest of his siblings (apart from toddler George) were listed as ‘Scholar’. ((‘Alfred Revill’ (1891) Census return for Winnowsty Lane, Lincoln, Lincolnshire. Public Record Office: PRO RG12/2594, folio 24, p.41. Find My Past (2013) Available at: http://www.findmypast.co.uk (Accessed: 21st February 2013). ))

In the 1901 census, when Alfred was 21, all of his siblings, apart from Elizabeth, still appear to be living at home. They were now living at 6 Motherby Lane, which is just around the corner from West Parade. ((‘Alfred Revill’ (1901) Census return for Motherby Lane, Lincoln, Lincolnshire. Public Record Office: PRO RG13/3062, folio 152, p.44. Find My Past (2013) Available at: http://www.findmypast.co.uk (Accessed: 21st February 2013). )) John is now a Journeyman Blacksmith, Alfred is a Coachman, Blanche is a General Servant, Walter is a Joiner’s Apprentice and George, now 13, is a Chemists Errand Boy. Elizabeth is listed working as a Domestic Servant in a house on West Parade.

Above: A Victorian Coachman ((Nanton, A.M. (1919) C. M. Wright, the Coachman, at kitchen entrance with Victoria and pair [Online]. Available at: http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/features/timelinks/imageref/ref0293.shtml (Accessed: 20th March 2013). ))

Ten years later, in the most recent census of 1911, only two of the children were still registered in the house with their parents. Alfred, now 31, was a Domestic Coachman like his father and George, now 23, was a Clerk in a Draft Office. Interestingly, there is another addition to this census; an 8 year old boy named Harold Starr who is registered as grandchild to Matthew Revill (Alfred’s father). ((‘Alfred Revill’ (1911) Census return for Motherby Lane, Lincoln, Lincolnshire. Public Record Office: PRO RG14/19744, folio 51, p.3. Find My Past (2013) Available at: http://www.findmypast.co.uk (Accessed: 21st February 2013). )) After some more searching it transpires that Blanche was Harold’s mother, registered with her husband Thomas Starr (Iron Planer) and their younger son Robert at 22 Hungate, Lincoln. So why was their eldest son staying with his grandparents and uncles instead of at home? ((‘Blanche Starr’ (1911) Census return for Hungate, Lincoln, Lincolnshire. Public Record Office: PRO RG14/19744. Find My Past (2013) Available at: http://www.findmypast.co.uk (Accessed: 21st February 2013). ))

The final piece of information I have found so far is a Marriage Certificate. In late 1925, in Lincoln, there was a marriage between Alfred E Revill and Mabel Atkinson. At the time Alfred would have been 45. ((‘Alfred E Revill’ (1925) Certified copy of marriage certificate for Alfred E Revill and Mabel Atkinson. Find My Past (2013) Available at: http://www.findmypast.co.uk (Accessed 21st February 2013). )) The house was built some seven years after they were married. Whether they were the first occupants remains a mystery. All I can determine is that by 1946 Alfred was living there alone.