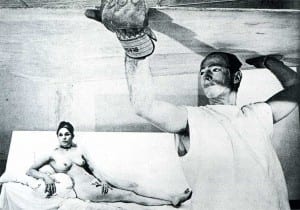

The bedroom is typically thought of as a place for sleeping, dreaming and sexual activity. Combining all three in our performance will cause an interesting reaction. Sexual fantasy and dreaming is an interesting topic and very little is known about the relationship between them. Freud created the notion that all dreams could be considered to have sexual references within them; it is all down to the interpretation. However, not all psychologists share this view. “The typical male dreamer has 12 “sex dreams” per 100 dream reports.” ((Domhoff, G.William (1996) Finding Meaning in Dreams: A Quantitative Approach, New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation.)) This is a relatively high number, considering dreams are a fairly regular occurrence for most people. Freud “also claimed that much of dream imagery represents repressed sexual instincts or desires.” ((King, D, DeCicco, T, & Humphreys, T 2009, ‘Investigating sexual dream imagery in relation to daytime sexual behaviours and fantasies among Canadian university students’, Canadian Journal Of Human Sexuality, 18, 3, pp. 135-146.)) Therefore, presenting a male voyeur with a sexually charged situation has the potential to make them conscious of their sexual fantasies.

Our performance separates the sleeping element and the dream content. The audience member in the bed is put to ‘sleep’ while the voyeur has the sexual ‘dream’ revealed in front of them. This shows a distortion between dreaming and sex. They are relevant and they can exist in the same place but people might not always remember a dream or it might not have an obvious meaning. This will only have this effect if the voyeur is a male. Males are reported to be “more likely to dream of someone other than their current partner.” ((King, D, DeCicco, T, & Humphreys, T 2009, ‘Investigating sexual dream imagery in relation to daytime sexual behaviours and fantasies among Canadian university students’, Canadian Journal Of Human Sexuality, 18, 3, pp. 135-146.)) Therefore, it will still be as effective seeing a naked stranger or acquaintance as it would be to see their own partner. It could be considered to be more effective as they might feel like they should be repressing their reaction.

Another interesting point to monitor on performance day would be the audience member’s interactions with each other. The person in the bed will be completely oblivious to anything else that would have happened and so will have to be informed by the voyeur. The voyeur might be very descriptive when describing what happened, or they might become embarrassed and leave out important details.