Hotel Medea (2011) CHAPTER II – DRYLANDS –. Online, http://vimeo.com/18224931 (accessed 24 February 2013).

Hotel Medea “allow for a participatory, immersive and interactive perspective of the theatrical event” ((Hotel Medea (2011) Hotel Medea Online: http://vimeo.com/hotelmedea (accessed 24 February 2013). )) within their work, and it is this immersive and interactive experience which we are trying to create, for both audience members, despite the fact the two audience members will never experience both performances. An example of Hotel Medea’s immersive theatre is their performance, Drylands.

In this durational evening performance, the audience became part of, and were offered an intimate part within the performance and it is this immersive, intimate and safe atmosphere which we are trying to inhabit in the bedroom. The experience will still be immersive for the cupboard…but not necessary safe.

|

|

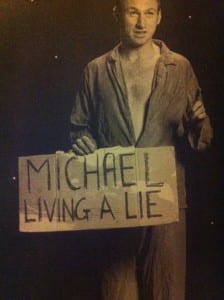

| Lauren Watson. Date taken: 22 March 2013. | |

As well as immersing the audience in the piece with spoken narratives and bed-time rituals, the room itself has been decorated and transformed by children’s drawings and paintings. The child’s room is safe and secure, with all the usual sexual context of the bedroom removed. We needed this essence of innocent and safety to be in the bedroom, as the cupboard which is built into the main wall holds none of these values. It subverts them, showing the true and heightened nature of what we associate with the bedroom. There is no safety or comfort to be found in the cupboard. You will find no bedtime story or hot chocolate to send you off to sleep to “the place in which we are allowed to dream” ((Heathcote, Edwin (2012) The Meaning of Home, London: Frances Lincoln Ltd., p. 76.)). What you will find is a narrative made to confuse, question and attempt to control you. It will put you in a position you would rather not be in, try and escape from, a place in which you wouldn’t want to stay.

“The remnants of site-specific performance can be extensive. It generates documents relating both the creation of performance and to the engagement with site before, during and after the event” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 191.)).

To let these two simultaneous events go undocumented would be a loss on our part as performers. The documentation “made during…often assert themselves to be the true record of what really happened, or else we ascribe that capacity to them” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 191-192.)), to be able to look back on what it felt like, and how we made people feel would ensure that we would not lose the performance entirely after the performance had finished. How many performances have you been to which take place in a house? And how many had you wished you’d been to? With documentation you would be given the chance to glimpse into the world we had created in our ‘safe house’.

“Site-specific performance as an unlikely and fleeting moment in history of a place, known only through the traveller’s [or audiences’] tales of those present” ((Pearson, Mike (2010) Site-Specific Performance, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 194.)).

Could we, as performer, document the performance and reactions during the periods in the performance where there were no audience members or visitors in our room? To have a note-pad and pen hidden in our space, at hand to record emotions, feelings, reflections and reactions would be invaluable.

Writing by tainted light, struggling to hold the pen in our greasy hands, struggling to move and see due to restraints. This would make the documentation as much part of the performance as we are. A living, breathing, active part of the performance. Just a part which no audience members will witness.