We use lighting all the time, whether it be to light up our house, to explore our surroundings or just simply to see.

Has light become a mundane feature of our lives?

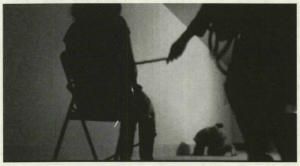

Anthony McCall’s light project You and I, Horizontal (2005), which was performed as an installation piece at the Hayward Gallery’s Light Show (2013) exhibition, explores the reality of light by literally showing the beams glaring across a plain black boxed studio room. These beams enabled audience members to change, adapt and become physically involved within the exhibition through being able to touch the rays and if felt the need stand in front of the light potentially creating moments of temporary darkness. Seeing as the projection was the only source of light in the room, the site appeared very surreal, this made the light, however slowly it moved the focal part of the performance. This changed the atmosphere and therefore took the conventional aid of light to another level.

Left: Artnet Galleries: The Light Show (2013) Accessed 5th April 2013

Right: BBC News in pictures: The Light Show (2013) – Accessed 5th April 2013

This exhibition used familiar and simple materials and ingredients but combined them to present a new creation. During the exhibition different audience members perceived the light differently, some seemed to be afraid, some were quite confident. This unusual behaviour created a sense of unknowing and difference in perception. Anthony McCall tends to strip back the environment to the bare essentials and due to his previous work using film projection he has said to “deconstruct cinema by reducing film to its principle components of time and light and removing the screen entirely as the prescribed surface for projection” ((Artabase (2007) ‘Anthony McCall’, online: http://www.artabase.net/exhibition/1530-anthony-mccall (accessed 4th April 2013). )) To discover that this artist had begun his work in cinema suggests that his works perhaps create a type of narrative. These narratives, as seen also in You and I, Horizontal , can be as vague as an emotion or idea that becomes something potentially more substantial as the performance continues. The fact that the site of performance is stripped back of all the components means that the audience can focus primarily on the meaning of the performance and their own interpretation of what it may be. The fact that each audience members’ experience of this installation can be different is very exciting and has a similar desired outcome to my work in Safe House.

Left: Tumblr; Anthony McCall (2013) – Accessed 3rd April 2013

Right: Anthony McCall: Installation view at Hangar Bicocca, Milan (2009) – Accessed 3rd April 2013

Anthony McCall’s “work in the Seventies had a more conceptual bent, nowadays McCall says that he wants to evoke the human figure — an effect underlined by the titles” ((Sooke, Alistair (2011) ‘Anthony McCall: Vertical Works, Ambika P3, London, review’, The Telegrpah, 4th March: p. 3. ) )) I feel as though his work evokes a potential abstract human essence within the space giving the site an unknowingly presence. Also I felt simultaneously that the art created a personal relationship with the audience through communication within the piece. This feature supported the personal individual response to the installation. I believe the real outcome of art is the response in which you have towards it. This reinforces the fact that the real piece of art, in this case, has intangible qualities which can rarely be shared from audience to audience.

The strange ability to touch the beams of light, due to a layer of aesthetic thin mist that filled the air, was a bizarre phenomenon. It felt as though the rules, conventions and traditional qualities of a light disappeared. The capability to see the beams for what they are and what they evoke inside of you as supposed to be used as a tool to view material vitalised the importance and the focus of the piece and therefore had a massive impact on your senses. Firstly your eyes were drawn to the projection. The focus on the room was very much the light but where in the room do you look? Do you wish to look on the wall where the light is projected or is there something about staring in to the hazy light that you would find appealing? Either way you look at this, separate performances appeared. For example as you stared in to the light you were ever so slightly blinded but due to the fact there were limited objects in the environment a feeling of harmony was achieved. Yes, occasional collisions occurred with other viewing audience members but all these emotions together created a sense of ‘a shared experience’. Another sense explored in this performance would be sound. The distorted sound of other audience members talking created quite an enjoyable backdrop to the performance. This sounds, however inaudible they were, made the piece feel connected with us as audience members as we could understand sections of text.

McCall, Anthony (2011) ‘Between You and I’, Ektoras Binikos, online: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-RpBPgWZQCw (accessed 4th April 2013. )

This sense is something I wish my audience to experience in Safe House – the ability to share an experience in such close proximity with an audience member but at the same time it be evoking completely separate ideas and emotions.

The notion that the audience are in control of the outcome is a main theme throughout my performance and research and this, similarly in McCall’s works, enables viewers to experience an individual performance and take from it separate ideas and emotions. This is great when analysing audience responses and letting the piece evolve in to something bigger and potentially new throughout the future.