As we continue through the creation process of our piece we seem to keep coming back to the concept of dreams. As we are performing in the master bedroom, I suppose it is unsurprising that we keep circling back to this subject. After all it is in our bedrooms that we sleep, and in so doing it is where we dream. It is said that “the strangeness of our night time narratives is actually an essential feature, as our memories are remixed and reshuffled, a mash-up tape made by the mind.” (lehrer, 2010) So if dreams are an essential feature in our lives then perhaps it is only natural that that we keep returning to the thought, because it is essential to the bedroom.

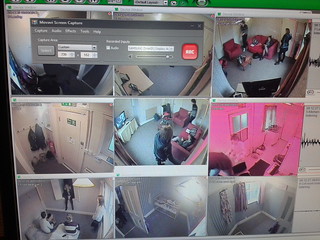

But how do we use dreams in our performance? We’ve had many ideas of how to go about this for example, having our dreams written on pieces of paper and then sticking them to the outside of the cupboard. Dreams are essential in the way that we grow, they help us commit necessary moments of our life to memory, and they help us work through emotional issues that we have. Therefore placing these fragments from our dreams on the outside of the cupboard would fit into our performance quite nicely. After putting one of the members of the audience to bed, in a childlike manner, and then forcing the voyeur to look at the image of a naked woman, bound in a cupboard would signify two extreme contrasts between childhood and adulthood.

Photo taken by Kayleigh Brewster

Therefore, by placing them in the cupboard door we could signify the process of growing up, the importance of dreams in that process and the connection between dreams and the bedroom. Placing the dream fragments there would also be significant as “according to Freud’s theory, dreams potentially communicated forbidden wishes and desires from the unconscious.” (Pick, 2004, 39) Whilst the naked body seems to be more frequent on the stage, the process of having that person naked, blindfolded, hand-cuffed and bound feels extremely taboo. Whilst books like 50 Shades of Grey written by E.L James or Sylvia Days Bared To You have brought other sexual practices to light, for example BDSM, the inclusion of these practices has given our piece a feeling of the ‘forbidden’ that fraud mentions.

In our performance the fact that the two female performers are hidden from view until a specific moment heightens the fact that what the ‘voyuer’ is watching something forbidden. When the ‘voyeur’ then realises the position that the two performers are in, that it connects with sexual practices that have only recently come to the forefront in literature heightens the link between fraud’s theory of forbidden desires in dreams, the visual aspects of having the dreams written out on the cupboard, and the vulnerable position of the performer in the cupboard.

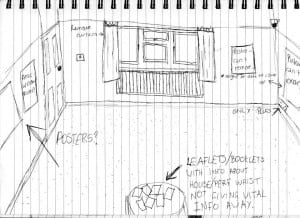

However we decided we wanted to make the cupboard seem completely separate from the rest of the room in order to completely separate the aspects of adult and child, and to make the opening of the cupboard a more dramatic reveal. So, what if we could make the bedroom itself seem dream like, without the use of words or covering the cupboard? What if we take pictures drawn in a childlike manner and cover the walls with them? That would make the room seem something other than normal and would still link to the original set up of putting the child to bed. Also, we began to focus on what the ‘parent’ performer would be saying to the audience in member who was being put to bed. What If we could make the narrative that the ‘parent’ performer speaks to the audience member like a dream?

Photo taken by Kayleigh Brewster

Works cited:

Lehrer, Jonah (2010) Why We Need To Dream http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/03/19/why-we-need-to-dream/ (last accessed 12/4/2013)

edited by Daniel Pick and Lyndal Roper Hove (2004) Dreams and history : the interpretation of dreams from ancient Greece to modern psychoanalysisNew York: Brunner-Routledge