It is completely normal to want to have a thorough understanding of the world around us and the way that most of us do this is to create categories, to organise things by function, appearance or by any number of unknown criteria in order to form neat groups. This building of taxonomies is part of our everyday lives, in fact my initial response to our site was to break it up into three such groups, The ‘Simulator’ includes rooms that have been made to simulate the feeling of home without actually being inhabited, the ‘Office’ category applies to those rooms that have no illusion of home and exist only to facilitate the illusion of the rest of the house and finally the ‘Home’ which can be used to describe those rooms that were left untouched as the house became a simulator and as such retained the traces of a true home. Each room in the house was then placed into one these three categories by its function.

Here we have the first point of interest the way we express this categorisation is through our only universal form of communication, language. For Saussure “Nothing is distinct before language” (( De Saussure, Ferdinand (1974) Course in General Linguistics, New York: Fontana Collins, p.111-112 )) so that part of our perception of an object is tied up in how we can describe that same object. You can only distinguish between things than can be described to be different.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nGlN_EaEgPQ

The clip above (( DuckPlumberThe2nd (2011) The Two Ronnies – The Confusing Library. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nGlN_EaEgPQ (Accessed: 9th April 2013) )) is the heart wrenching tale of the compulsion to classify gone horribly wrong, the man is completely unable to find his book because of the monstrous disregard the librarian appears to have for a logical taxonomy (though it must be remembered it was in fact the architect’s idea). This fable does however raise some serious questions, why is it absurd to order books by colour, size or thickness? It seems it is all a matter context, which is a quite vague answer and definitely requires further scrutiny. The aim here then is to challenge the pattern of classification, to ask which criteria we choose and why. Why is it any less valid to be looking for a large green book than for The Twisted Spur?

The most obvious answer is that we define things by function because that is the most immediate way in which they will relate to us. How can I use this item? It does not matter to us what colour the item is if we currently need it to mash potatoes (unless of course you are an architect).

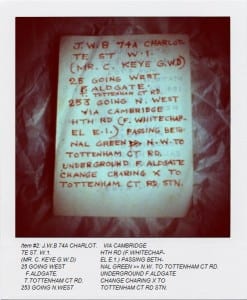

What happens then when an item is rediscovered? I.e it’s use is unknown, then it is a matter for the historian or archaeologist to place it in a taxonomy, the first step towards this is describing the item, here the job of the historian/archaeologist seems reasonably simple they must “articulate it into a description acceptable to everyone: confronted with the same entity, everyone will be able to give the same description; and, inversely, given such a description everyone will be able to recognise the individual identities that correspond to it” (( Foucault, Michel (1970) The Order of Thing, London: Routledge, p. 134 )) . Obviously there are huge challenges in creating universal taxonomy and Foucault further advises historians/archaeologists to describe using only what can be observed as fact or by use of “by analogies that must be of the utmost clarity” (( Foucault, Michel (1970) The Order of Thing, London: Routledge, p. 134 )) .Then we go back to Saussure to the idea of the sign, signifier, signified which relies, as Foucault observes, upon “the common affinity of things and language with representation” (( Foucault, Michel (1970) The Order of Thing, London: Routledge, p. 132 )) he continues however “things and language happen to be separate” (( Foucault, Michel (1970) The Order of Thing, London: Routledge, p. 132 )) .

It is here, the space between signifier and signified, in which we can successfully incorporate the performer, for it is his (my) job to take the idiosyncrasies of the world and expose them. So if we take the job of classification away from the so called expert (the historian/archaeologist) and hand it over to the performer (who then becomes the performer/historian/archaeologist) what might we discover?

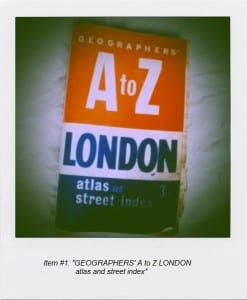

Let’s start with something as simple as the category of ‘things that were found in this garden’. While that is what binds each and every one of my exhibits together, can there be more to it than that? What happens when we throw off this context, take those items out of their immediate context and place them somewhere else, somewhere neutral, a museum perhaps? What links those objects now? I (performer/historian/archaeologist) know that these objects originate in the same place but if the language that accompanies the exhibits, the language that is responsible for their context refuses to supply it, the audience is forced to make their own taxonomies of the seemingly disparate. What connects the bird feeder and the plug socket, the cigarette lighter and the hat stand? These are the questions the audience must be encouraged to ask, and then logically the nature of our classifications as a whole.

The exhibits are connected by one abstract factor, none the less they belong in the same category according to this particular performer/historian/archaeologist. This should then ask, in societies quest for order and definitive answers, what are the possibilities we overlook?

This shed is like the office or lab it is a place in which to retreat into thought, it is a shrine, the domain of the expert, the place where he plies his trade, makes his assumptions with divine tunnel vision. If, as Saussure assures us, there is no distinction without language then what effect do the lies/mistakes of the performer/historian/archaeologist have on the nature of the object? That we will have to find out in performance.