Performance artist Andre Stitt here talks about how he uses certain substances in is performances as representation for feelings/ emotions etc. Some of the substances he uses are chosen based on personal memories of his, like the use of tar and feathers. At the end, as the narrator points out, he pushes the boat he has covered in certain substances out into the sea and it can be seen as a release or “letting go” of the dark memories he and/ or the audience possess. Straight away this struck me, in relation to what I have been working on in the bathroom.

In his book, At Home: A short history of private life, Bill Bryson talks extensively about plague and disease in history and how a great deal of it has related to being unclean and not washing. In his chapter about the bathroom, he discusses how people in the Middle Ages thought that to “plug the pores with dirt” ((Bryson, Bill (2010) At Home: A short history of private life, London: Black Swan)) was the best way to protect themselves from plague. “Most people didn’t wash, or even get wet, if they could help it – and in consequence… Infections became part of every day life… serious illness accepted with resignation” ((Bryson, Bill (2010) At Home: A short history of private life, London: Black Swan)). Nowadays, obviously, we are aware of the fact that quite the opposite of this is true. We wash daily, to clean – or purge – ourselves of dirt and grime gathered through the day, and to prevent ourselves from smelling and getting ill.

This idea of purging made me think of Andre Stitt’s work as a kind of purge also – like in his performance Where the Grass is Greener as seen in the video above. How the ritualistic aspects of his performances – with the feathers and pushing the boat out into the sea – help him let go or purge himself of unpleasant memories or feelings. How could I apply this to the bathroom?

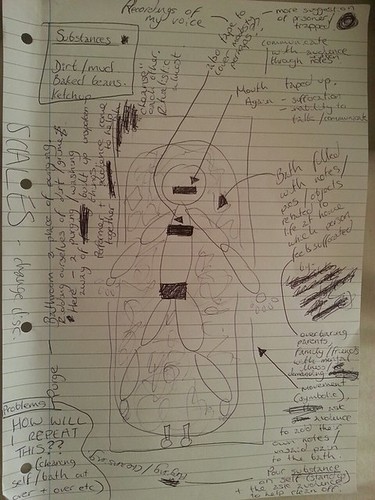

After spending some time in there and sketching out some thoughts (as can be seen above), I tried to apply my previous ideas of how home life, or people within your home life can make you feel suffocated there. And how, more often than not, it is impossible for us to talk about these issues because we are just supposed to put up with them, or we think we are, if the people involved are family or people we love. Examples of this include overbearing/ strict parents (not necessarily physically abusive but perhaps), children with behavioural problems, loved ones with long term illnesses or even mental illnesses (like depression etc). I played with this idea of things we can’t say that grate on the inside of us, and how some sort of action or ritual within the bathroom could help us release this, or purge ourselves of it. (after all, as we have discussed, the bathroom is a place of purging anyway).