Every Sculptor , like every performer, must to some degree tackle the questions of site, ‘what am I creating?’ and ‘how will it interact with its surroundings?’. There are artists that put this concern at the forefront of their work, their site is their stimulus, their source of material and it defines their work.

Within these artists there is further distinction, which element of the site is it your sculpture aims to subvert/complement/interact with?

In 1979 a group of sculptors undertook a commission to create site inspired sculpture around the campus of the Wellesley College Museum, Stehpen Antonakos was one of the artists commissioned, his unique response was rooted in the pre-existing architecture “in terms of its formal stylistic features” (( Hoos Fox, Judith (1980), Aspects of the 1970s: Sitework, Boston: The Wellesley College Museum , p. 3 )) . His final piece Red Incomplete Neon Circle (pictured here) completely breaks up the straight oppressive geometry of the existing building, creating a new dialogue between the conflicting angles.

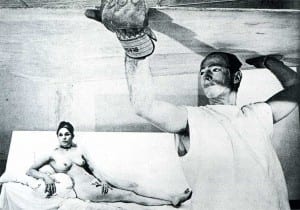

This dialogue between architect and sculptor then transforms the entire building into the art work, forcing the observer to re-assess what was took for granted before, this is then a prime example of site art; It both responds to and enhances the site on which it is built. Antonakos’s ideas, however, are somewhat distant from my own, he focuses on the finished product, assembling it in his own workshop off site. My work needs to take shape before the audiences eyes, the sculpting itself and the possibility of collaboration within that makes it not simply site art but also site performance. It is a single artists visual response to a visual stimulus, as such it is a simple piece, which hold resonance only if we wish to think about the structure, there is so much more to site which we can access however.

Another artist tackles the same question with a very different process. Lars Kordetzky travelled to a decommissioned psychiatric hospital shortly before it was to be demolished, in order to create an artistic response to the site. He began building sculptures that would suggest the psychological footprint of the isolation cells former inhabitant. Using the drawings of a former inmate Kordetzky began to understand that to this inhabitant the room was not as small as it seemed, instead he found complex mesh of worlds built in “a different scale for different mental dimensions” ((( Kordetzky, Lars (2001), Saw Only The Moon, New York: Springer-Verlag Wien, p. 80)) . In isolation the patient had created numerous worlds within his cell, invisible to all but himself, consisting of whole towns connected by an impossible network of tunnels. His sculptures (one of which is pictured below) start with a cuboid frame, then gradually he begins to build up each individual world of the patients imagination, the picture below (( Koredtsky, Lars (2010) Sequences: Saw Only the Moon Online: http://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2010/01/23/lars-kordetzky-sequences/ (Accessed 6 April 2013) )) shows one such world which has clearly been ripped into three by the fragmented nature of the patients grasp on reality.

Kordetzky recognised that the worlds and towns that the patient had created were not fully formed, each one bled into the next, this “Architecture of blurredness” (( Kordetzky, Lars (2001), Saw Only The Moon, New York: Springer-Verlag Wien, p.86 )) as Kordetzky calls it is shown translated in to the sculpture as wood and plastic intersect and interrupt each breaking through the imagined barriers of the worlds, none are enclosed or separate, each is forced to interact with those around it. The Effect of looking through one of Kordetzky’s sculptures is then to perceive the world through the eyes of the patient, within the frame there is such a chaos of these intersecting worlds that the frame is no longer obvious, the observer like the patient can no longer see the physical boundaries, which form the metaphor for walls of the isolation chamber, but are enraptured by the contents, the insanity of the interior. Kordetzky then accurately recreates the psychological landscape of his site and most importantly for my own work, roughly half way-through the process he asks the inmate to come and assist with his work. This is of course the only person that can help Kordetzky, being the only person with any actual knowledge of what is being recreated.

The Shed is a place for thinking, “Spaces we construct in which to dream” ((Heathcote, Edwin (2012) The Meaning of Home, London: Frances Lincoln, p.114)) and here is the similarity, the isolation cell serves to isolate the individual and confine his madness, while the shed exists to facilitate the thinking. They leave a somewhat similar psychological footprint, that of place which is a concentrated centre of thought, dreams and creativity, the only difference being that between the rational and the irrational, which is quite possibly, not such a huge distinction after all. Kordetzky when concluding his project explains that the inmates “eternal struggle for home, means creating structures of one’s own” (( Kordetzky, Lars (2001), Saw Only The Moon, New York: Springer-Verlag Wien, p. 24 )) these structures are psychological for the inmate but could just as easily be made physical. Indeed men in their hobbies often build models, jigsaws, spice racks or even as the patient does whole towns of their own, perhaps in as literal a form as a model railway. Both are spaces which exist primarily for thought and dreaming, the only difference is between the necessity of the isolation room and the luxury of the shed.

Because of these similarities there is more in my project to sympathise with the process of Kordetzky than Antonakos because like Kordetzky’s project, mine seeks to go beyond the physical remnants of site into something which is not immediately obvious, it calls upon the subjective experience of the individual co-inhabiting the site.

As I have mentioned in previous blogs the aim of this half of the performance was specifically to settle the question: ‘how are men perceived?’, but in light of the kind of work that was undertaken by Kordetsky, I feel it might be appropriate to focus the question a little more upon dreams, so for now the question is “How do we build a dream, from the comfort of home?” and these dreams belong to everyone, so it makes sense to invite anyone to to contribute to the sculpture as it slowly develops.