“Like his voice can’t deal with things it has to describe, That’s the thing you have to do with a voice after all – make it speak of the things you cannot deal with- makes it speak of the illegal ” ((Tim Etchells (1999). Certain Fragments. New york: Routledge. 98-176))

What if you take away all the voices? What if a performance has no words, no specific message and is completely open to the audience’s interpretation, but surely silence has meaning?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bm_tTkHooZI

In this you tube video, the university student talks about the value of silence and quotes her professor he describes how “Every individual structures their attitudes, beliefs, lifestyle, and behaviours around a theme. What is the life philosophy by which you live, and how has it shaped you as a person?” She goes on to say that her theme is the value of silence and of a quiet mind, she explains that “It’s something that I think is particularly relevant to modern youth, because the observation of silence is not something that our generation engages in enough” What happens when we explore the diversity and difficulty of silence in different situations? People like to focus on words and sounds, because they are comfortable words make a house feel homely. People are scared of silence, they are obsessed with noise they find it difficult to be alone to just shut the curtains; lock there doors. People are afraid because it is unfamiliar, when you isolate yourself there is no where to run.

She also says “I don’t think that practicing silence is necessary for observing silence. It has to do more with having a quiet mind than physically immersing oneself in silence” In our performance as our piece is a durational performance and we are going to have to have a quiet mind and physically immerse our self into our performance in silence.

Tim etchells talks about the meaning of silence, he made a list of silence of different situations

“ These are some examples of the list of silences

The kind of silence you sometimes get in phone calls to a person that you love.

The kind of silence people only dream of.

The kind of silence that follows a car crash.

The kind of silence between waves at the ocean”

Some examples that really interested me and relate to our room are…

“The kind of silence after a big argument

The kind of silence that only happens at night

The kind of silence is only for waiting in” ((Tim Etchells (1999). Certain Fragments. New york: Routledge. 98-176))

What if you took the kind of silence that is only for waiting in, and put it in a homely environment? Would that make the audience feel uncomfortable would they feel like there waiting for something? Our audience may feel that they are waiting for something to happen in our performance but it never does.

What if you left a room waiting?

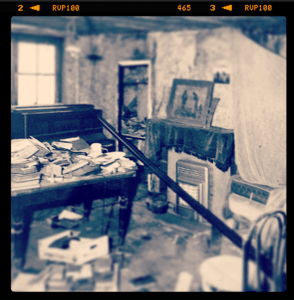

“The atmosphere still retained the oppressiveness of a religious space; it seemed natural to speak in whispers. I felt my way along the corridor and opened the door at the end. The peeling paintwork of the synagogue was lit by warm yellow candlelight” ((Rachel Linchtenstein and Iain Sinclair (1999) Rodinsky’s Room: an excerpt http://www.artangel.org.uk//projects/1999/rodinsky_s_whitechapel/excerpt/excerpt (acessed: 10 April 2013)))

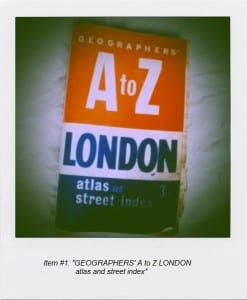

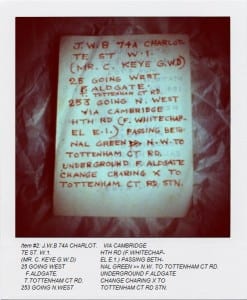

Rondinskys Room is story of what became of the reclusive Jewish scholar David Rondinsky, whose room at 19 Princlet street London was discovered undisturbed and had been left for 20 years after. As I was reading and researching into the story I found myself asking the question what silence would you call the silence of a room left alone to gather dust for 20 years be? Going on from what I was saying earlier about “the silence of waiting” I feel that this is the silence that applies to his room. When we go on holiday our house is waiting for us to come back, to make it home again. I feel that when I come home after being on holiday my house seems different smells different, sometimes even looks different we have to adjust ourselves to that space and learn to live in it again. Rondinskys room was waiting for him to come back to come home but he never did, and was found by somebody else someone that it wasn’t familiar with. I feel that this added to the atomosphere in the room, and if we can create this kind of feeling for the audience in the living room it will be a very frightning and awkward situation for them to be in.