How did we play with the power that our room gave us? We exploited it. We use the visual information that we could see to our advantage and took on authoritarian figures to fit the context. Due to the nature of our safe house a spy like persona was taken on by the actor welcoming the audience members to the house before they explored the house one room at a time. To solidify her role in the eyes of the audience the CCTV team adopted similar roles as “agents”, engaging with the audience over the phone, questioning them about their appearance and safety having only seen them over CCTV. While this role had little to do with our installation piece it gave us the opportunity to perform live on the night as well as supervise our installation and actually the ‘agent’ role fitted the supervisory role that we would have needed to be anyway.

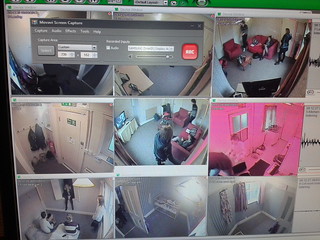

I think what was particularly effective about our room was what our installation was able to show the audience: the space as it would be when once everyone had left and all the lights were turned out. Marita Sturken writes that “installation that deploys such technologies as video and computer devices delineate time” ((Erika Suderburg (2000) Space, Site, Intervention: situating installation art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. P. 287 ))and I think that our piece can identify with that. The videos on the computer screens showed the space that they had just explored in a different time, in a different light, with different inhabitants and with a different purpose, and for me, that juxtaposition with the image of one screen showing live CCTV footage of the nine rooms in colour and fully inhabited was just what the piece needed.

Before the performance when the nerves set in I found myself more focused on what the audience would think of the live performance, not the installation, because in the live performance it would have been easy for something to go wrong. The improvised phone conversations were nerve racking at first as there was no way to rehearse that part of the performance. However due to the nature of the phone call it became easier to know what to say and how to say it as each member of the audience came through, making the questions I asked not only original, but more effective.

Prior to the performance I was concerned about how I would react if an audience member tried to address me, as the role I was playing was intended to act as the eyes of the room and only interact with the audience when asking them to leave. In the event no one did try to interact with me which I now think was a shame as I would have loved to take the character further and inform the audience that “I am not permitted to divulge that information at this time.”. However the fact that I remained un-distracted enabled me to observe the reactions and interactions to the installations that were occurring around the room. If the audience spoke to each other at all they did it in a whisper, which I think reflected the mood of the room. It was interesting to see that they perhaps feared the consequences of talking out loud in a room full of whispering voices. Only one pair discussed their experiences in the other rooms and this pair was the only pair who did not really acknowledge me at all.

The performance itself was both exciting and tiring. It was empowering to take on an authoritative role for the evening, yet daunting to have to improvise a phone conversation with someone that I could see but that could not see me. It was fascinating to see how the audience reacted to the months of planning various rooms had put into their performances and it was unbelievably exciting seeing everyone pull off their performances to such a high standard. It was also gratifying seeing how the audiences reacted to our installation and of course how they reacted to the live CCTV stream of the rest of the house.

Overall I think everyone involved in the project should be extremely proud of the work that they have produced. As a group and as individuals we have created a piece of work like nothing seen before and like nothing that will ever be seen again and it is an experience that none of us will ever forget.