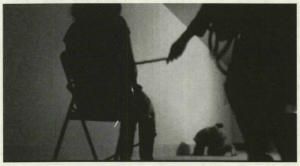

In my final performance I cried. I found my way into hysterics. This is because I had female voyeurs in the chair. My friends who know and love me…and who cried first.

When I heard their sobs, it made me realise my situation – that I was actually tied, bound and gagged in a cupboard, naked and completely vulnerable. At first it wasn’t too bad, just a few tears and silent sobs. But by the second female voyeur, we both ended up in hysterical sobs. I had to keep looking at them, the voyeur, my friends in the chair, but it became impossible. By the end of the second female voyeur, I had to cover my face and cry into my hands just as the cupboard doors were closed.

The experience left me shocked, shaken and very emotional. I had never expected to feel like that, I had always expected that the male voyeur would be harder…to look a man in the eye and exert dominance. But to feel empathy from a fellow woman, and to reduce each other to tears is something completely different, unexpected and exceptionally unique and moving. Just like it Marina Abramović’s work, my “audience became genuine co-creators of the performance” ((Freshwater, Helen (2009) Theatre & Audience, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 63.)). The reactions by all voyeurs, male and female, were triggered by me. My body, and my voice. “You are the topic…You are the centre. You are the occasion. You are the reasons why” ((Freshwater, Helen (2009) Theatre & Audience, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 1.)), and all these reactions were different. Some men knelt, some studied the pictures around the room with forced intensity, some looked away, others looked confused, sad, and some looked me over.

It was a shame that I couldn’t record the voyeurs reaction to me, my body, my voice. After all, I was getting filmed and observed, so my emotional breakdown was seen not only my the voyeur, but also by the CCTV crew, so it is a shame that the voyeur was in the CCTV blind spot, so only I could see their reactions. I am the only one to see their reactions, and will be the only one. That moment will never be re-shown or re-lived, making it truly a once in a life time experience. The submissive having all the knowledge, and therefore power is honestly an empowering, yet juxtaposed, position.

“When should you be naked and when should you be dressed?

What is performance?

What is the performance body?

…What is your responsibility to your audience?

If the performance is performed again, what are rules?

What is the role of the audience?

Silent voyeur or active participant?

What about reputation?” ((Marina Abramović (2010) ‘Foreword: Unanswered Questions’ in C. Conroy Theatre & the Body, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. viii-x. Pp. ix-x.)).

These questions caused anxiety, especially in relation to the naked body and reputation. I thought it would most difficult to perform to lecturers and men, as I would have to see them again afterwards, and I was worried about my reputation and the working relationship which had been previously developed would be forced to change. However, on the evenings of performance, these turned out to be the easiest. Although initially scared, I began to enjoy the performance; watching their reactions and their discomfort, and final submission was empowering.

Were the audience “just viewers, or accomplices, witnesses, participants?” ((Freshwater, Helen (2009) Theatre & Audience, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 3.)). In relation to our performance in the bedroom and cupboard, the audience can be seen as all four. The house as a whole challenged the audience/performer relationship, and changed the pre-established dynamic. As they entered our performance space, the audience are unknowingly turned into accomplices and witnesses; witnessing the hidden adult world of the bedroom, while also becoming an accomplice to the performer in the bed, viewing and examining the female form in the cupboard. As performers, we knew what relationship we wanted to forge with the audience; “the relationship with the audience provides the performance with its rationale. This relationship is indispensible” ((Freshwater, Helen (2009) Theatre & Audience, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 2.)).

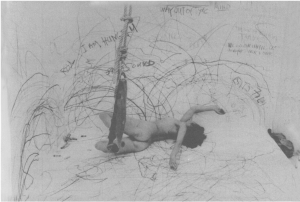

Pushing past my personal boundaries, often being pushed rather than walking willingly, while dealing with nudity, the body, and eye contact have definitely shaped me, not only as a performer, but as a person. It’s interesting that at the beginning of this entire adventure I stated that when I was younger, the cupboard was the place which shaped me, and made me grow up faster than I should have done. So to have this experience mirrored is a little disconcerting, but also comforting. This process, although difficult at times, created a moving and unique performance. Not just in the cupboard, but in the bedroom as a whole. By supporting and pushing each other as performers, we managed to create something which we were incredibly proud of, and something which will never be performed again.

“Presence. Being present, over long stretches of time, Until presence rise and falls, from Material to immaterial, from Form to formless, from Instrumental to mental, from Time to timeless” ((Marina Abramović (2010) ‘Foreword: Unanswered Questions’ in C. Conroy Theatre & the Body, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. viii-x. P. viii.)).

Although we have left the house, our rooms and our performances, our presence will always be felt in that house on West Parade. How the rooms were transformed and broke away from the conventions of a ‘house’. The cupboard will now always be tainted, at least in my eyes. A place which created its own meaning and now stirs its own memories.

This experience, this journey, and the barriers I have overcome during this process…nothing can compare to it. And I don’t think it ever will.