“As in life, actors need to be aware when staring at others is and is not appropriate” ((Schiffman, Jean (2005) ‘Eye to Eye’, Back Stage West, XII (22), 1531572X, May: N.P.)).

Eye contact in performance is vital. It establishes relationships between performers whilst also forming a relationship between the audience and performer/s. But what happens when this eye contact deconstructs or challenges a pre-established relationship? Forced or prolonged eye contact alters the dynamics of a performance, often leaving either recipient or instigator feeling uncomfortable, scrutinised or even exposed.

In our performance, it this surprisingly, usually easy and expected convention of the theatre that is becoming our biggest fear and ask.

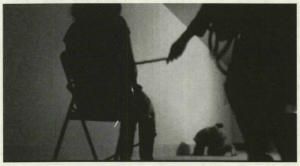

“In the theatre, gesture appears typically in conjunction with spoken text, underlining, undermining or counterpointing it” ((Scolnicov, Hanna (2010) ‘Stripping as Gesture’, ASSAPH: Section C: Studies in the Theatre, XXIV, pp. 139-152, p. 140.)), however, in our performance we are playing with this convention. Subverting it, almost. The eye contact happens in silence. The performer is unable to speak, yet the eye contact becomes justified and essential. To hold eye contact is to hold the power within the scene or scenario. But when this scene is subverted, the eye contact becomes a challenge in itself. To create power where there was none through eye contact is an intimidating task, and to subvert a strong, dominating relationship through eye contact alone is empowering.

|

When we are hidden behind the blindfold, we become an object to be viewed. Aspects of the ‘actor’ are stripped away, and we become a possession, as “beneath the mask the actor hides not merely his face but also his identity” ((Scolnicov, Hanna (2010) ‘Stripping as Gesture’, ASSAPH: Section C: Studies in the Theatre, XXIV, pp. 139-152, p. 142.)). The audience knows us on merely an aesthetic level. A possession to be viewed. Although the identity of the performer is not known, the scene presented to the audience is still an intimate one. “Looking at someone is almost like touching them” ((Schiffman, Jean (2005) ‘Eye to Eye’, Back Stage West, XII (22), 1531572X, May: N.P.)), and when that person has no power to look back, this notion of touching them is heightened.

To subvert this power balance without the use of direct address is really an electric moment. “To deconstruct language is to deconstruct gender; to subvert the symbolic order is to subvert sexual difference” ((Showalter, Elaine (1989) Speaking of Gender, London and New York: Routledge, p. 3.)). Suddenly, through the abandon of language, our sexual difference has been subverted, with all the power handed over to us, the exposed performer. This “female self-unveiling substitutes power for castration” ((Showalter, Elaine (1992) Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siecle London: Virago Press, p. 156.)), castrating the voyeur (if male), removing all previous power he held. When we remove our blindfold, the male gaze becomes scrutinised and challenged and abhorred.

This transference of power, and a ‘one-on-one’ audience/performer situation is similar to Allison Wyper’s Witness (2010-2011). Witness is a “participatory performance for one audience member at a time in which the viewer is configured as accomplice to the performance event, a ritual in which power is borrowed, trafficked, and stolen” ((Wyper, Allison (2011) ‘Witness: Notes from the Artist’, Platform, VI (1), pp. 57-76, p.57.)). By participating in this transition of power and status, we make ourselves vulnerable, and question where we stand within the performance.

“As we watch others we are also conscious of being watched” ((Wyper, Allison (2011) ‘Witness: Notes from the Artist’, Platform, VI (1), pp. 57-76, p.62.)).

The behaviour of both performer and voyeur changes throughout the performance. Although first making eye contact is intimidating and scary, once our gaze restored, the power balance shifts. Suddenly, the object looks back and takes on a persona. Challenging the roaming gaze of the voyeur. In our practical sessions, the voyeur has held our gaze. This is either out of respect or fear. Fear to be seen looking at you naked and totally exposed, but also because you are owed respect.